Welcome to the latest edition of the medical news. Each week we bring you three key healthcare topics that have recently been under the microscope.

This week’s topics:

Last Chance IVF

Morbilliviruses and Mammalian Transmission

Eating Disorders on the rise

IVF

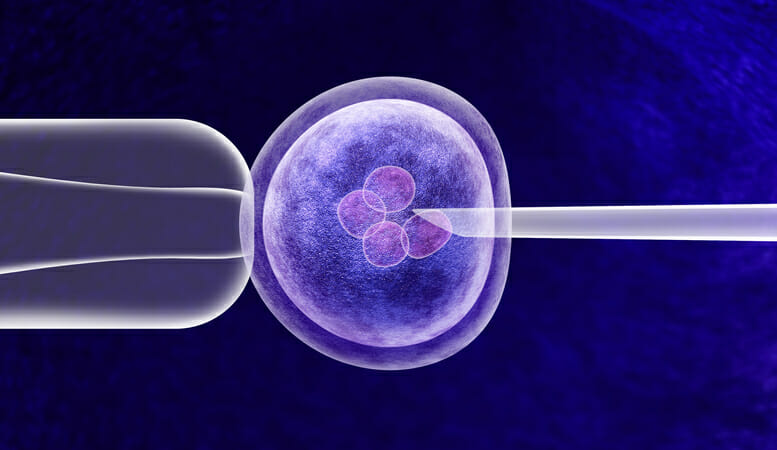

After fifteen rounds of IVF, and calling time on their treatment implanting one last embryo, a couple took home a healthy baby boy in mid-December.

After spending £80,000 on In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) treatment over a six-year period, Lewis and Hannah Vaughan Jones (both 38) conceived, carried, and gave birth to their son Matheson last month. The couple made the decision for one final attempt following medical advice, after taking into consideration the emotional and financial drain of the treatment. They stated that they had no real hope going into it. They had tried so many times that statistically, it was unlikely to work, and they were ready to move on. They also said that paying for the treatment made them feel “emotionally vulnerable” after each successive failed attempt.

What can we learn from this?

IVF is unsuccessful in 70% of cases, taking around four to five years to conceive on average. Women under 35 see the highest success rates, with one-third of treatment cycles being successful. This story encapsulates the debate on whether or not the NHS should offer more cycles, as the possibility of conception remains after each attempt – a pertinent medical ethics discussion.

IVF is also expensive, with one cycle costing upwards of £5000, so the NHS limits the number of cycles of the treatment eligible people may receive. Through private healthcare streams, there is no set cut off with how many cycles may be attempted if a patient has enough viable eggs to continue. However, doctors should advise stopping when they feel the odds of success are too low to merit continuing.

Question to think about: What other aspects should doctors consider and discuss in terms of a patient continuing or stopping IVF treatment?

Morbilliviruses and Mammalian Transmission

Morbilliviruses, including measles, are found in mammals are largely adept at transmission between different species. Measles is part of the morbillivirus group – a group of highly related viruses – and is capable of transmission between different mammalian species. The common ancestor of the measles virus is thought to have originated from a bovine virus, and canine distemper virus (CDV) is thought to have arisen from the human measles virus.

At the moment, the primary factor in the prevention of animal morbilliviruses spreading to humans is the pre-existing immunity we have built against the measles virus. However, reductions in vaccination uptake and increasing outbreaks are increasing the risk of cross-species spread.

What can we learn from this?

The UK lost its ‘measles-free’ status in August 2019, after only three years of elimination, which has been attributed to the decline in uptake of the measles vaccination (Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) in the UK). Coverage for the MM2R vaccine dropped for the fifth year in a row in 2018-19 to 86.4%; down from 87.2% in 2017-18. The WHO recommends coverage of at least 90% to provide effective herd immunity and prevent outbreaks of disease. It’s not just measles though, the potential for other morbilliviruses to affect us reinstates the importance of continuing the measles vaccination program.

Question to think about: How would you improve the uptake of the MMR vaccination in the UK?

Eating Disorders

Figures show that hospital admissions as a result of eating disorders have seen an increase of 37% across all age groups in the past two years.

In 2016/17, there were 13,885 hospital admissions for eating disorders, rising to 19,040 admissions by 2018/19. Data from England showed that the most common age-group for anorexia-related admissions in 2019 was 13-15, with a quarter of all admissions for children aged 18 and under.

What can we learn from this?

Whilst there have been improvements in the care available to young people with eating disorders. Children and young people are still finding difficulty in accessing the care they need before reaching the point of hospital admission. By providing early support, there is a better chance of both the prevention of escalation and of full recovery.

Question to think about: Why might we be seeing more cases of eating disorders at a younger age, despite increases in the care available?

Words: Nea Sneddon-Jones

Want weekly news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up to our newsletters here!

Previous editions of The Medic Portal’s Weekly News:

Weekly Medical News – December 19th

Weekly Medical News – December 12th

Weekly Medical News – December 4th